WHAT DOES THE DATA SAY?

Only three studies included in the literature review, two from the United States and one from Denmark, examined access to work among persons with deafblindness [4, 19, 20]. All found barriers to engaging in employment, although sample sizes were small and not representative of the broader population. Some challenges highlighted included difficulties transitioning from school to work, the need for vocational training [20], and early retirement following the onset of deafblindness in older age [19].

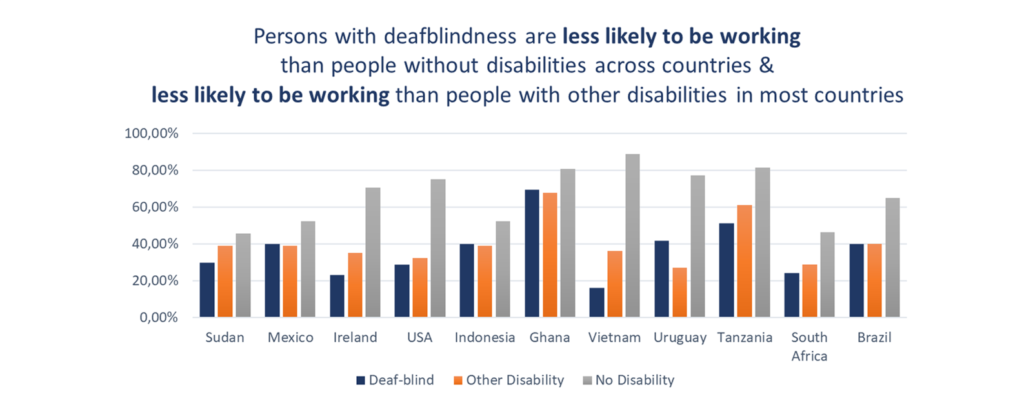

Figure 8 compares the working status of persons with deafblindness, people with other disabilities, and people with no disabilities across the datasets. Specifically, the survey reports on whether or not the respondent has undertaken any work for cash or in-kind payment over the last 12 months. The findings are restricted to persons of working age (15 to 64), excluding those currently in education.

In comparison with people with no disabilities, persons with deafblindness were statistically less likely to be working across all 11 datasets. Participation rates among persons with deafblindness tended to be higher in low-income settings compared with high-income settings. For example, only 23% of adults with deafblindness in Ireland and 29% in the United States were working, compared with 70% and 75% of people without deafblindness respectively. In comparison, gaps in participation rates in Sudan (a gap of 15%[1]) and Ghana (11%) were lower. This trend was inconsistent, however, as high gaps in participation were also evident in Indonesia (55%) and Vietnam (73%).

Excluding Uruguay, where the sample size was too low for age-stratified analysis, people with deafblindness across all age groups were statistically less likely to be working than people without disabilities in all datasets except Sudan, where there was no statistical difference in the 15 to 29 age group (see Figure 9 overleaf). In comparison to people without disabilities, the gap in participation appears to increase with age, and is most pronounced amongst older adults in high-income settings.

Compared to people with other disabilities, persons with deafblindness were statistically less likely to be working in seven of the eleven datasets (Sudan, Ireland, United States, Vietnam, Indonesia, Tanzania and South Africa), after controlling for age and gender. However, younger people with deafblindness were statistically more likely to be working than younger people with other disabilities in the United States and Brazil, with no statistical differences evident for this age group in other countries. People with deafblindness aged 30 to 49 were statistically less likely to be working than people with other disabilities in Ireland, Tanzania and South Africa, and more likely to be working in Ghana and Brazil. In the oldest group of working age adults (50 to 64), people with deafblindness were less likely to be working than people with other disabilities in Ireland, the United States and South Africa.

There were no consistent trends between men with deafblindness and men with other disabilities, but women with deafblindness were less likely to be working than women with other disabilities in seven of the eleven datasets (Sudan, Ireland, United States, Tanzania, South Africa, Indonesia and Brazil), after controlling for age and gender.

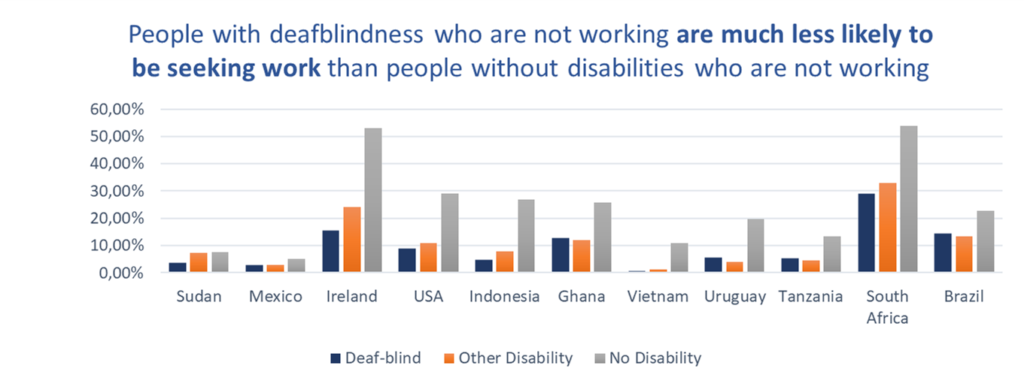

Amongst people of working age who were not working, people with deafblindness were much less likely to be looking for work than people without disabilities, and this was statistically significant in eight of the eleven datasets. People with deafblindness were also statistically less likely to be working than people with other disabilities in three datasets (the United States, Indonesia and Vietnam), and more likely to be looking for work than people with other disabilities in Brazil.

It is important to note that this data does not account for work security or type of work. For example, in many low and middle-income countries, the informal economy is the main source of employment. While it is easier to find informal work, employment is typically less stable, lower paid and does not offer protections for workers (e.g. sickness/accident insurance, pensions or representation) [21]. There is evidence that people with disabilities are overall more likely to work in the informal sector [21], which is therefore likely to be similar for persons with deafblindness. Additionally, persons with deafblindness may be less likely to work if they have access to social welfare and benefits. For example, in the study conducted in Denmark, while only 8 of the 163 (5%) people with acquired deafblindness between the ages of 18 and 64 years were employed, 63% were receiving the country’s disability living allowance [4].

OUR VOICE

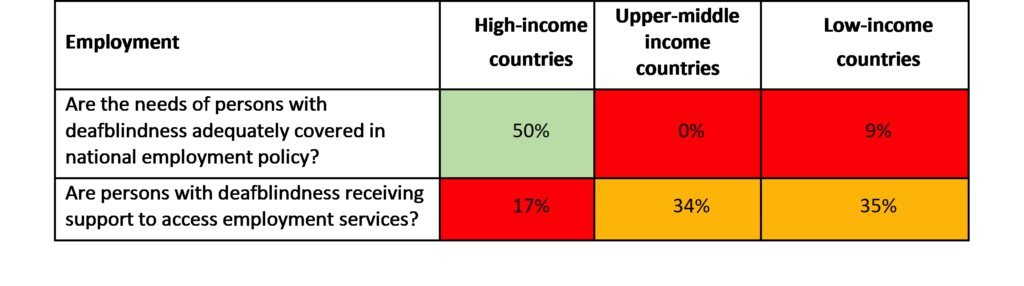

The majority of WFDB members had a negative perspective of the efforts made by governments to ensure equal opportunities to work and employment for persons with deafblindness. Whilst half of all respondents from high-income countries stated that employment policy adequately covers the needs of persons with disabilities, only 17% felt that appropriate employment support measures were in place. Members highlighted discrepancies between policies and implementation.

WFDB members from low and middle-income countries stated that employment policies do not really consider persons with deafblindness. However, services do exist to support those in work, especially in relation to livelihood and self-employment. The differences between higher and lower-income countries can be attributed to the fact that employment in lower income countries is typically informal with little social protection support. In high-income countries, however, significant barriers to work exist in a mostly formal labour market. As a result, many persons with deafblindness may receive disability benefits, which are often determined by resource threshold or incapacity to work criteria.

WFDB members from different countries highlighted several common issues:

- There is a critical link between education and employment: Scandinavian countries provide a good example of governments investing in high quality education for children with deafblindness. This empowers children, gives them confidence and provides them with the necessary employability skills. In the majority of countries, however, a lack of adequate education, orientation and mobility training, daily living skills for children and young people with pre-lingual and post-lingual deafblindness, severely limits employment opportunities. In addition, few countries offer effective career guidance, internship and job placement services that could build a bridge between education and employment.

- Prejudices of employers. Attitudes constitute a major barrier for many persons with disabilities, but are magnified as a result of a lack of awareness about the communication requirements of persons with deafblindness. This is compounded by a lack of government support for interpreter-guide services, which may significantly increase the cost faced by employers who hire persons with deafblindness. It is clear that, in countries where governments pay for interpreter-guide services, persons with deafblindness find it easier to gain employment. Quota and tax incentive policies could theoretically help; however, the issues outlined above significantly reduce the potential positive impact. Examples were shared of companies employing persons with deafblindness to achieve tax breaks and subsequently not offering them meaningful work or telling them to stay at home.

- A lack of recognition of deafblindness as unique disability. This leads to people being excluded from legislation in many countries, such as in Bolivia, where employment law does not mention persons with deafblindness. Often persons with deafblindness are not included in vocational training and employment programmes for other persons with disabilities.

- Few countries reported that their respective governments were financially supporting interpreter-guide services in the workplace. This significantly reduces the inclusion of persons with deafblindness in the labour market.

- In a number of countries, persons with deafblindness face restrictions in terms of legal capacity. For example, a bank may require a person with deafblindness to have someone present to sign a contract in order to open a bank account. This limits individuals’ ability to manage their finances and engage in economic activities.

A study carried out by Sense International in Peru in 2018 concluded that the main barrier to the employment of persons with disabilities, and persons with deafblindness in particular, is the prejudice of employers and co-workers. The study recommended that work placement measures should not focus on a ‘typical’ job that persons with disabilities could do, but that people are provided with support to find work that matches their profile and aspirations. It also highlighted the importance of the use of ‘internal mentors’ as an effective approach to ensure the sustainability of inclusion. The implementation of Law No. 29524, which recognises deafblindness as a unique disability and mandates the state to promote the training and accreditation of interpreter-guides to support people with deafblindness, was identified by the study as a vital development. The study also recommended the introduction of incentives to encourage companies to do more to include persons with disabilities, in particular persons with deafblindness, since current tax benefits are insufficient and have not made an impact.

WFDB members also described a range of interesting practice, such as persons with deafblindness who are in employment offering peer support and mentoring to those looking for work.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ensure that persons with deafblindness are adequately included in employment-related laws, policies and programmes.

- Ensure the adequate provision of interpreter-guides for work and employment.